Aamir Khan, XLRI Jamshedpur

h20062@astra.xlri.ac.in

HR Analytics became a buzzword found in articles on the future of work in general and HR in particular. There is no denying the fact that it has a huge potential to be unlocked. And Covid acted as a catalyst in unlocking some of that potential right away.

This article examines how HR Analytics has been used to disrupt the measurement and analysis of culture, a critical and challenging task that organizations need to perform to remain relevant—the article first analyses traditional ways of measurement, followed by the more recent techniques.

There is a famous saying, “culture is what happens when the lights are off.” The management guru Peter Drucker has famously said, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Larry Fink, the chairman and the CEO of the American multinational investment management company BlackRock, writes to the CEOs the things organizations need to do to remain relevant in the future. In 2018, the letter talked about purpose and long-term value creation (culture is a critical element of long-term value creation). In 2019 again, Fink urged the CEOs to focus on purpose to reap long-term benefits (Fink, L. (2019)). Not surprisingly, there is an increased focus from investors and regulators alike to assess a company’s culture. Culture diagnosis is becoming an essential part of the due diligence done by investors before investing in companies. In fact, in the UK, it is almost mandatory to assess culture. The Financial Reporting Council revised the UK Corporate Governance Code to include board responsibility to monitor and evaluate culture (FRC. (2018)).

The question is, how do we assess something as fluid as culture? There are two ways of doing that. The more traditional ones are statistical and collect data using surveys and questionnaires. The drawback with this approach is that organizations are in a state of constant flux, and these surveys measure culture at a point in time. In other words, such measures are static or episodic. Other ways use advanced analytical techniques that use big data to scour the digital trace of the employees to measure and analyze culture. This article first examines the more traditional survey approach and then the more modern big data approach.

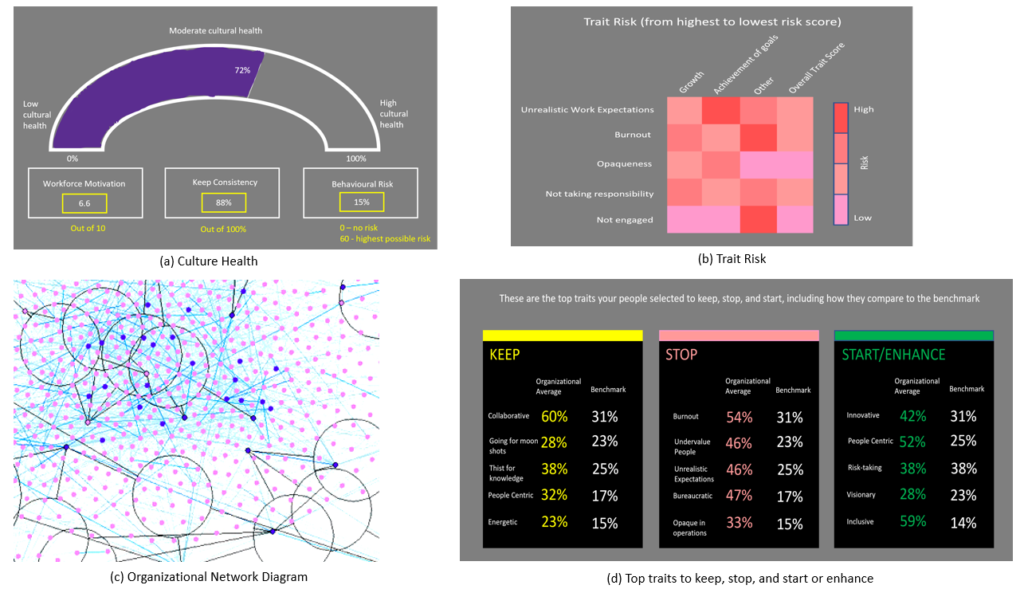

Organizations have used surveys for over a decade now to measure, analyze, and report culture. Off-the-shelf SaaS solutions are available, which can be customized to the organization’s needs, but many organizations have put in the resources to develop their own internal assessment tools. Whenever an organization does any culture assessment, it must be able to look at what is it that it needs to encourage and do more of (value creation), and what is it that it needs to get a proactive alert on (value protection), so that it can stop that before it eats the organization away. Shown below is a sample output of such a culture assessment diagnosis.

Figure 1Source for (c): Wikimedia Commons

The organization needs to understand its cultural health. In the case of the figure given above (figure 1a), the organization has a cultural health index of 72%. There also needs to be an understanding of workforce motivation: what factors keep the workforce engaged and wanting to continue working for the organization. This includes but is not limited to questions like what the employees really like about working for the organization, whether the work makes good use of the employees’ abilities, etc. That forms the workforce motivation score. Positivity or keep consistency are things that the organization is doing well that need to continue. For example, employees may be given several traits of which they have to select, let’s say 7 traits that define the organization. Each of these traits is tagged as a positive or a negative trait. When the overall survey result comes, it can be judged whether the organization is more positive or negative.

Behavioural Risk is about value protection. For example, if there are instances of harassment being reported, then that is a behavioural risk. The organization needs to be concerned, even if these numbers are small. Trait risk is like a heat map of behavioural risks (figure 1b of the figure).

Organizational network analysis (figure 1c of the figure) can also be done, and it shows the hubs (individuals or departments) that are of high influence. One application can be to identify change champions when trying to affect change in the organization. To affect change, one needs to establish a sense of urgency for change, followed by forming a powerful coalition that pushes the change forward (Kotter, J. P. (1995)). The network diagram can be used to identify potential members of this powerful coalition.

Keep, stop, and start/enhance is a table (figure 1d) which respectively shows what parts of the culture need to be maintained, stopped, or started if they do not happen presently. When the organization focuses on creating something novel in its culture or enhancing an existing positive part of the culture, it focuses on value creation.

While the method mentioned above is neat, it is nevertheless static. Throwing a bunch of traits that might describe the organization on your employees and asking them to select the accurate ones is subject to bias. There are also differences reported when the same employees choose the traits at different points in time. This hints at the episodic nature of such a static diagnosis.

More advanced culture diagnosis happens using big data to track your employees’ communications on emails or internal direct messaging tools of the organization. Some interesting insights have come up using such analysis on an individual and organizational basis, which was previously impossible using static analysis.

There has been an explosion of digital communication data since the pandemic outbreak, as most of the work happened from home and employees connected using emails and chats. Harvard researchers Matthew Corritore, Amir Goldberg, and Sameer B. Srivastava conducted research to exploit big data to analyze culture (Matthew Corritore, A. G. et al. (2020)). Some interesting insights emerged.

Firstly, culture is fluid and keeps evolving. Hiring decisions focus on current cultural fit, but what is equally important is to understand that ‘adaptability’ – the ability of the employee to adapt as the organization’s culture changes owing to its fluid nature – is as essential as ‘fit.’ Secondly, and surprisingly, there are benefits to not fitting in. The researchers give an excellent prescription of when to hire a cultural misfit. The people who do not identify themselves as part of a group bring in new ideas and innovations that boost creativity. Though cultural fit was strongly correlated with success, the misfits also had an advantage because they had strong social bonds within small groups, allowing them to leverage their uniqueness. The prescription thus is to hire a mix of cultural conformists and misfits.

These insights were impossible to attain using the static organizational network diagram shown in figure 1. A dynamic analysis using big data threw light on how organizations’ networks formed and evolved in the larger cultural setup, interacting with the culture, affecting it, and getting affected by it. Such analysis has scope of understanding when the culture may be taking a negative turn and then take measures immediately to rectify it. But despite the benefits, there are ethical considerations. Having access to employees’ emails and chats on workplace messaging apps entails risks, and strict confidentiality must be maintained. Security issues also exist, and clear guidelines must be in place for such an analysis to take place.

Overall, while the pandemic has pushed advanced techniques like big data to measure and analyze culture, it comes with its own set of risks. It is not supposed to be a trade-off as compromising employees’ privacy to gain accuracy in measuring culture can never be an option. Nevertheless, the benefits of technology in people management are plenty, and the example of cultural assessment shown in this article is just one of them.

References:

- Fink, L. (2019). LARRY FINK’S 2019 LETTER TO CEOS. Retrieved from BlackRock: https://www.blackrock.com/americas-offshore/en/2019-larry-fink-ceo-letter

- FRC. (2018). 2018-UK-Corporate-Governance-Code-Final. Retrieved from frc: https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/88bd8c45-50ea-4841-95b0-d2f4f48069a2/2018-UK-Corporate-Governance-Code-FINAL.PDF

- Kotter, J. P. (1995). Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail. Retrieved from HBR: https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2

- Matthew Corritore, A. G. et al. (2020). The New Analytics of Culture. Retrieved from HBR: https://hbr.org/2020/01/the-new-analytics-of-culture

Posted in Students Corner | No Comments »

Recent Articles

- Leveraging Analytics for Measuring and Analyzing Culture

- The New Age HR- Rethinking People Management using Tech & People Analytics

- Culture driven by core values

- Dispelling the fear of failure: Nurturing innovation & experimentation

- Smart Failures: Why Embracing Failure is Key to Experimentation and Innovation

- It Is Team Work That Matters!

- Redefining the hiring recipe: Recruiting candidates beyond the resume!

- Recruiter’s Dilemma: Getting hold of the pain-points in prevailing strategy is the key to restructure the hiring recipe